Sharing mothering experiences past and present

In the 1970s it felt like all sorts of new opportunities were starting to open up for women. Germaine Greer’s book The Female Eunuch, published at the start of the decade, caused controversy as it talked about the oppression of women in contemporary society and stated that sexual liberation was the key to women’s liberation. Hard as it may be to believe now, this was a time when married women still needed their husband’s permission to be fitted with an IUD.

In 1975 Shirley Conran wrote a book called Superwoman, a book for busy women, which featured a quote much loved by the housewives of the day – “Life’s too short to stuff a mushroom”.

Nothing is new under the sun

However, as much as each generation loves to think it is the first to come up with ideas, history tells a different story. Today’s newspapers and magazines like to publish articles discussing the choices women make, but 100 years before Greer wrote her book, writers of the day had their opinions on feminism and motherhood.

Surprising as it may seem, in the 1870s and 80s books and newspaper articles appeared questioning the role women were expected to take in life. In a world which sounds remarkably familiar, families felt they were in an era of uncertainty; worried by trade recession and political upheavals in Europe. In 1877 a controversial article appeared in the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine entitled “Have We Too Many Children?”. That same year a pamphlet called The Fruits of Philosophy – about the techniques of family planning – was accused of being an obscene publication and the press had a field day arguing for and against this, with respectable women being told to block their ears to the discussion.

Expanding horizons

Some of the main support for feminism came from men. One of its champions was called Thomas Wentworth Higginson and in 1882 he wrote a book called Common Sense about Women1. In it he exclaimed “Do not drown in your child, do not sacrifice your own work”. With education opportunities opening up for women, who were now allowed to attend university lectures (although they weren’t considered capable of taking a degree) many felt reluctant to settle down to motherhood.

Naturally there were those who fought back against this. A woman called Mrs Bowdich was a great believer in maternal instinct and believed that a mother’s confidence in her own instinctive feelings were being undermined. This sounds remarkably similar to the discussions we hear today. Mrs Bowdich bemoaned the increasing popularity of a young baby being cared for by someone who was not its mother and called it unnatural. In Confidential Chats with Mothers2 she said a young baby needed the love of a mother’s heart and the tender shelter of her arms.

The swing against breastfeeding

Naturally breastfeeding was a big part of the debate and there was a swing against it. There were claims that artificial foods were just as good, if not better. In statements which could just as easily come from current articles writers commented that a hundred years before it was rare for a woman not to breastfeed. Now women were asked “How do you feed him?”

In another example of a strangely familiar scenario, a Mrs Panton3, well known to be anti-breastfeeding, commented that it may have been “natural” in the past but times had changed and people had to adapt. She suggested that a mother should not condemn herself to be a “cow” unless she really wanted to nurse, and she knew only too well the misery of nursing a child.

Bombarded by opinions

The parents of the late 1800s were bombarded by just as many theories and studies on raising children as today. Some advised more indulgence and others extolled the virtues of discipline. Pamphlets were issued on infant care and they didn’t hold back on strong opinions. One proclaimed that dummies were “an invention of the devil to tempt others to harm their children.”

The Swing Back

By the early 1900s things were changing yet again. In 1907 the St Pancras School for Mothers was established and held sessions called Babies’ Welcome which seem to be the first baby clinics. Breastfeeding was recommended and breastfeeding mothers got free dinners!

Women who wanted to embrace motherhood had felt under fire from the feminists of the day and so were delighted when a Swedish author called Ellen Key wrote the Renaissance of Motherhood in 19144. In it she raged against the yearning to be free from the essential quality of womanhood – motherliness. She said that ‘each young soul needs to be enveloped in its own mother’s tenderness, just as surely as the human embryo needed the mother’s womb to grow in, and the baby the mother’s breast to be nourished by.’

She also opposed the idea of state creches or nurseries, believing this encroached on the mother’s role, and that the mother was the child’s best educator.

The Debate goes on

The debate on the role of a mother did not end there of course. It continued throughout the 20th century with women of the day, keen to do the best for their children, often being influenced by the current theories of scholars, psychiatrists and scientists.

Many now familiar names such as Sigmund Freud, Jean Piaget, John Bowlby, Margaret Ribble and Truby King offered their thoughts on raising children. They were followed by others such as Benjamin Spock, Hugh Jolly, Penelope Leach and Penny and Andrew Stanway (the latter were favourites of La Leche League, attending several of our conferences in the 1980s). I could happily fill columns with fascinating quotes from child care manuals!

And so to the 70s

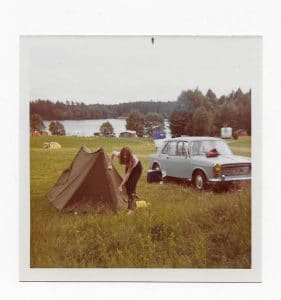

For now, to return to the 1970s, when my own mothering journey began.

The 60s and 70s were an exciting time of change for young people. A new era of music had begun and I remember a trip on the school bus with half my class chanting “Beatles” while the other half shouted “Rolling Stones”. The hippy era really appealed to me and I happily wore flowers in my hair and a bell around my neck. Early music festivals were amazing experiences – although basic in the extreme; two burger vans and a tent filled with open plan toilets were the extent of the facilities at some!

Despite the need for much greater equality, most women still expected to get married and have children. While couples were starting to live together without being married it was still referred to as “living in sin” – and “shotgun marriages” (where the woman was pregnant and the father was expected to marry her) were still common. In the past, it had been common practice for unmarried mothers to be hidden away and forced to give up their babies for adoption, but things were starting to change and women were fighting against the prejudice and deciding to keep their babies. However, the stigma against women who had babies “out of wedlock” would continue for some years, and may even continue in some places today.

At this time it was not unusual for a woman to be married and have a baby in her late teens or early twenties, something else which was more than familiar in the 1800s. In 1836 William Alcott had written a book called “The Young Mother”, which discusses the “Management of Children in regard to Health” and is still available now. He also wrote a book entitled “The Young Husband – Duties of a man in the marriage relationship”!

When I had my first child before I was twenty I was not the first in my peer group to become a mother and I remember one women who was having a baby at the same time as me being called an “older mother” at the grand age of 26 much to her annoyance!

By the early 1970s breastfeeding rates had crept up to 28%, but that included babies who only went to the breast once or twice and most mothers assumed they would bottle feed. Many childcare manuals of the day also trod a cautious path in this area. They paid lip-service to breastfeeding but were careful not to say anything which would make mothers “feel guilty” if they didn’t, which in turn made mothers think they probably wouldn’t. The cycle of society giving women the idea they would not breastfeed, but leaving them feeling guilty when they didn’t, was well established.

As I started on the road to motherhood I was feeling excited that I was going to have a baby. While in today’s society women often prefer to wait and do other things before starting a family – or chose not to have one at all – I had been planning my imaginary family since I was thirteen and I couldn’t wait to be a mother.

More next time on pregnancy in the 1970s.

1 Higginson, Thomas Wentworth, Common Sense about Women, Bell, London, 1882

2 Bowdich, E.W., Confidential Chats with Mothers on the Healthy Rearing of Children, Balliere, London 1890

3 Panton, Jane Ellen, From Kitchen to Garret, 4th edn, Ward Downey, London 1888

4 Key, Ellen Karolina Sofia, Renaissance of Motherhood, Putnam, New York and London, 1914

Sources:

Dream Babies, Child Care from Locke to Spock, Christina Hardyment, 1983

Further reading:

https://laleche.org.uk/dummies-and-breastfeeding/

https://laleche.org.uk/dummies-and-breastfeeding/#why

https://laleche.org.uk/birth-breastfeeding/